Cities of Tomorrow: Improving sanitation and hygiene services in Babati, Tanzania

This blog explores the SHARE research our partners at WaterAid in Tanzania have been working on. The blog was originally written and posted by Joseph Banzi and Priya Sippy on 19 December 2018. Joseph is Senior Program Manager Research and Knowledge Management at WaterAid Tanzania, Priya is Communications and Campaigns Manager at WaterAid Tanzania.

2.3 billion people currently live without a decent toilet of their own. Increased urbanisation means that the inclusion of sanitation and hygiene services in urban planning is key. WaterAid Tanzania’s Joseph Banzi and Priya Sippy discuss findings from a two-year research project into urban sanitation.

70% of Tanzania’s population currently live in rural areas, but that percentage is changing rapidly as more towns expand and move towards city status. This change puts added pressure on Tanzania’s already stretched water and sanitation services. When water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) systems are left out of city planning, it can force communities to rely on unsafe sources of water, inadequate latrines and unsafe mechanisms for pit-emptying, all of which subsequently expose citizens to unhygienic environments and behaviours.

Research and methodology

In 2016 WaterAid Tanzania began a two-year research project in collaboration with Manyara Regional government, Babati Town Council (BTC), Babati Water and Sanitation Authority (BAWASA), and Nelson Mandela African Institute of Science and Technology (NMU-AIST). The research aimed to find out the current sanitation and hygiene situation in Babati, determine stakeholder motives for investment in those services and analyse different sanitation and hygiene options for the town.

Our research included:

- observation of key hygiene behaviours carried out in 179 households;

- focus group discussions in schools and communities;

- political economy analysis comparing the situation in Babati to the towns of Moshi, Bomang’ombe, Temeke and Arusha;

- the completion of a ‘Shit Flow Diagram’ for Babati, based on mapping the sanitation coverage and practices of Babati’s 20,000 households (using mobile technology).

The desired outcome of the research was to come up with an action plan for sustainable sanitation and hygiene services in Babati Town, home to 90,000 people, as well as informing the development of Babati Town spatial master plan.

Research findings

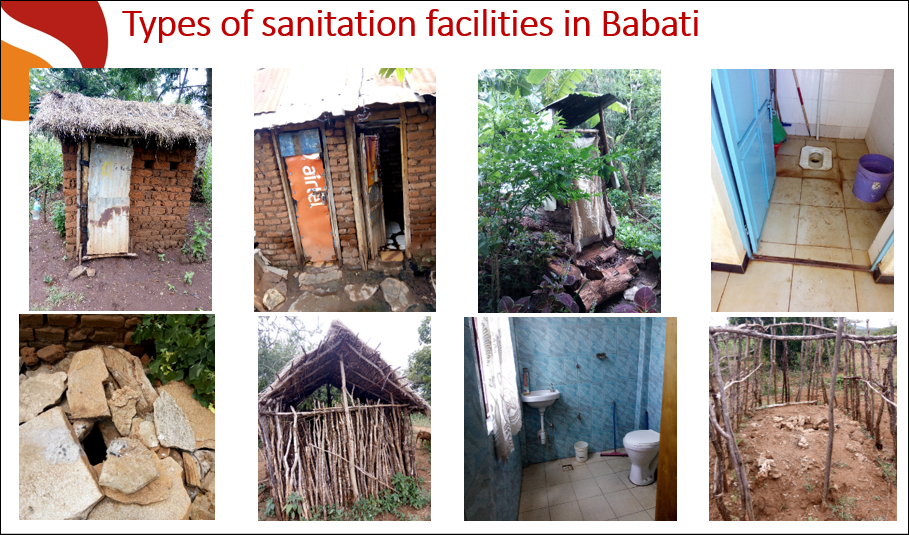

Our findings show that 90% of Babati’s households have toilets, 63% of which are pit latrines (some with a slab), and 33% of which have flush/pour flush latrines. Just 4.3% of households have ventilated pit latrines.

The management of wastewater in Babati town depends entirely on onsite sanitation systems composed mostly of septic tanks and pit latrines. Research reveals that 31% of households are managing faecal sludge safely, with potential health and environmental risks. Most of Babati's individual toilets cannot be emptied, or go for long periods without being emptied.

Around 94% of households do not have handwashing facilities with soap and water close to the toilet or in the kitchen. Although 97% report washing their hands after using the toilet, we observed just 46% of participants actually practicing that behaviour. Approximately 70% of respondents said they understood and practiced proper disposal of child faeces, but only 50% were observed disposing of children faeces appropriately. Additionally, 55% of respondents reportedly don’t treat their drinking water by boiling the water or using purifying tablets, putting them at risk of water-related diseases.

The research also determined three key motives behind a wish for improved sanitation:

- enforcement of existing rules and regulations;

- fear of diseases;

- the need for a safe environment.

The key motivations for practicing hygiene behaviours, such as handwashing with soap and having an improved latrine, were:

- disgust (i.e. at having dirty hands);

- nurture (practicing behaviours for the future of their children);

- attraction (practicing behaviours to appear smart, clean or 'pure')

- taste of food (i.e, if food is cooked or re-heated properly, it seems tastier);

- children eat more food;

- financial status of the individual/household;

- bylaws for reinforcing hygiene behaviour, for example if you do not have a toilet you will get a fine.

Scenario planning

Following the research, key stakeholders from the national, regional, district and community level came together to discuss different sanitation and hygiene scenarios for the town.

Stakeholders discussed the pros and cons of faecal sludge management (FSM), sewerage and alternative sewerage options, and decided that FSM is the most appropriate option for town sanitation. This means that the sludge produced in households shall be frequently emptied by mechanical or manual means, and transferred to a treatment plant where the by-products will be recycled. One example of FSM we have already implemented in Dar es Salaam is the Faecal Sludge Treatment Plant (FSTP), which transforms liquid and solid waste into bio-gas and compost.

In terms of hygiene scenarios for Babati Town, we aim to improve the following behaviours:

- handwashing with soap;

- household's water treatment and storage;

- use and cleanliness of sanitation facilities;

- food hygiene;

- waste management.

Turning research into practice

One of the initial outcomes from the research is an agreement by town planners to include sanitation and hygiene in future Babati city planning. In the town’s ‘spatial master plan’ the chapter on sanitation now reflects some of the research findings, which will help to ensure that the appropriate sanitation services are considered when it comes to planning the growing town.

The next step for the town is to put together an action plan for sanitation and hygiene services based on the agreed scenarios, and then mobilise resources to implement the plan. We will continue to support Babati as they move forward with their action plan.

Whilst urbanisation can present a lot of opportunities, it also throws up many challenges. This research demonstrates the importance of embedding sanitation and hygiene systems in town planning, and will hopefully be used to encourage and influence other growing towns in Tanzania. It also illustrates that effective planning and stakeholder collaboration can help to ensure Tanzania’s cities of tomorrow have sustainable access to sanitation and hygiene.