Progress in integrating WASH and food hygiene in Malawi

Kondwani and one of the study participants in Chikwawa district. The study participant is wearing a chitenje, t-shirt and wristband given out as part of the Hygienic Family intervention.

As mentioned in our previous blog, SHARE has returned for a third phase, where we’ll be focussing on ensuring the research findings currently being published by our partners have impact on WASH policy and practice locally, nationally and globally.

I recently travelled to Malawi to work with our partners at the University of Malawi (Polytechnic) WASHTED Centre who are working in collaboration with the Malawi Epidemiology and Intervention Research Unit (MEIRU). They are now at the exciting stage of analysing their primary outcome data.

Their work focuses on integrating WASH and food hygiene in Malawi. This is a crucial area as contaminated food may be an important driver of childhood diarrhoea which persists as a leading cause of child deaths (WHO, 2017).

MEIRU’s innovative study which started in January 2017, and is co-led by Dr Tracy Morse and Kondwani Chidziwisano, aimed to design, implement and evaluate the effectiveness of food hygiene and WASH interventions in preventing childhood diarrhoea in Chikwawa District, Southern Malawi.

The results from this research will have important implications for governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and multilateral agencies working in the WASH, nutrition and child health sectors. Regardless of the direction of the results, they can be used to help improve the quality of future community-based programming that aims to reduce childhood diarrhoea.

Read on for a summary of what MEIRU have done so far and where they’re at now.

Intervention design

The research team first carried out formative research. This was conducted in 323 households which were not included in the study and was based on the RANAS model of behaviour change.

A recent publication – Chidziwisano et al. (2019a) – describes the findings of this formative work around risk factors associated with feeding children under two in rural Malawi. A further paper – Chidziwisano et al. (2019b) – describes how the team identified key behavioural, cultural, socio-economic and environmental factors that were increasing risk of diarrhoea in children.

The team identified pathways and routes that were leading to exposure to diarrhoea causing microbes. They also collected baseline data within the population recruited for the study and carried out a literature review.

Intervention

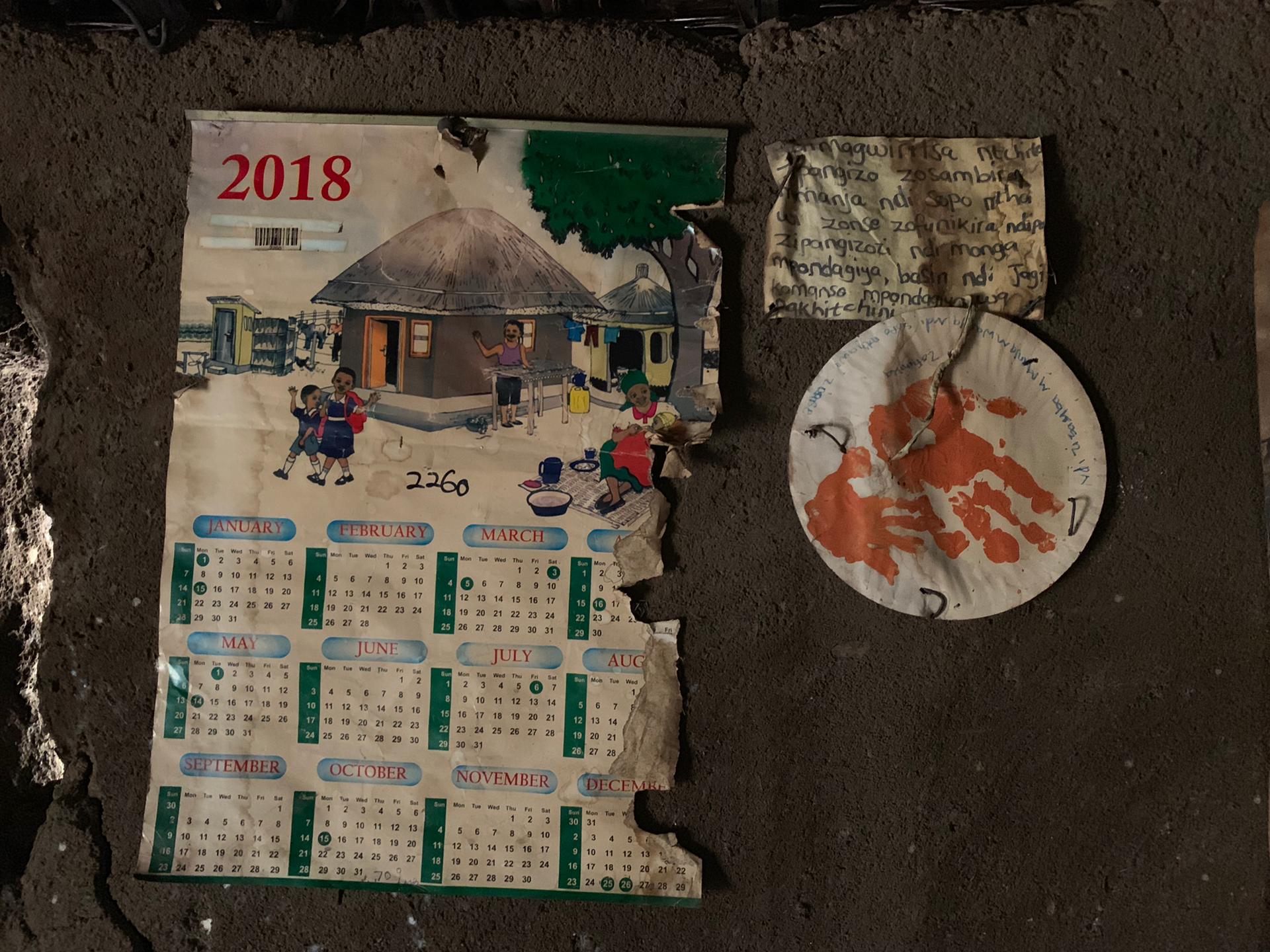

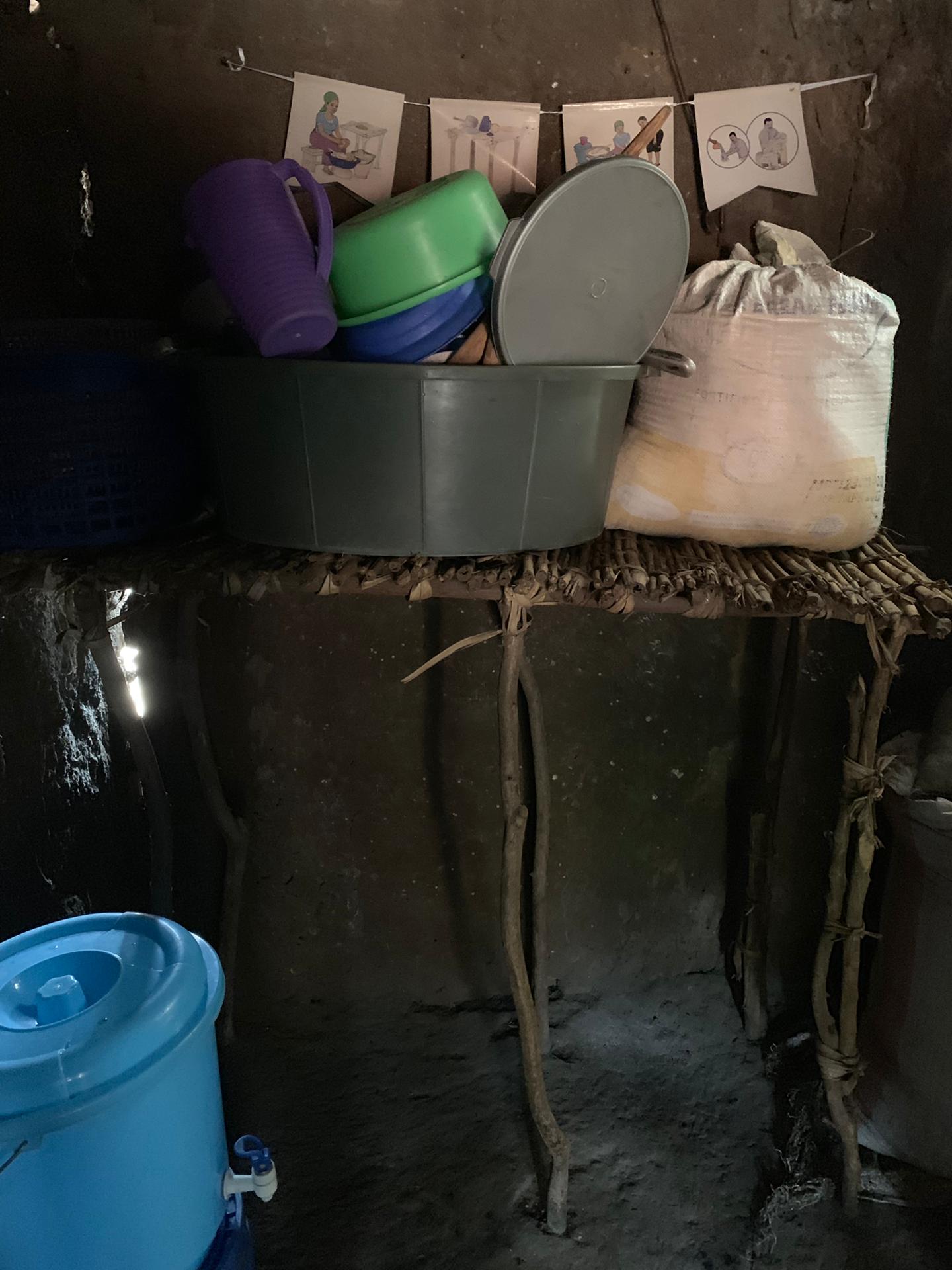

The research team’s earlier findings led them to develop behaviour change interventions targeting four key behaviours: handwashing with soap at critical times, food hygiene, household water management and faeces management.

Together, the packages were known as the Banja la Ukhondo (Hygienic Family) intervention since the intervention targeted all family members.

A cluster randomised control trial was conducted in Chikwawa district over a period of 12 months. 1000 households were allocated to one of three arms: one of two “treatment” groups or the “control” group”.

In one of the treatment groups, only the behaviour change interventions around handwashing and food hygiene were implemented, whereas the other treatment group received all of the four behaviour change intervention packages. This was to assess whether food hygiene practices alone would be enough to reduce childhood diarrhoea.

Implementation of the Hygienic Family intervention began in February 2018. The research team recruited ‘key informants’ – community volunteers who each facilitated meetings with approximately 20 caregivers of the children enrolled in the study in both the treatment and control groups.

One week the key informants would hold meetings discussing key practices of one of the behaviour change packages, the next they would follow up in the households of the study participants to check how these actions were being implemented and the following week they held meetings to discuss what they learned (both positive and negative) from implementing practices.

This process was repeated until all four packages of the intervention had been delivered. The process evolved iteratively as meetings were held after delivery of each package to assess if anything needed changing, and allowed participants to share challenges and successes for peer based learning.

Records were maintained by caregivers on a daily basis to provide data on children’s health status.

Challenges

There were some challenges the team faced during their study.

The rural study area was prone to long periods of drought and flooding, since it is low-lying. This meant it was difficult for the villagers to harvest enough food, meaning they often received food subsidies from NGOs. Initially, it was difficult to encourage the study participants to work with the team, since they were not receiving food items.

There was also some misunderstanding around why the researchers were collecting microbiological samples. However, through working closely with local leaders, the team were able to explain the premise and importance of the research project and the need for collecting samples.

Although the intervention was designed for all family members, encouraging men to attend meetings for the project was difficult because of pressures on their time and their feelings towards their roles in household hygiene. The team overcame this challenge; empowering women to improve their households by teaching them to build handwashing facilities (amongst other things).

Evaluation and next steps

The end of project evaluation started in November 2018 and involved observations, household surveys, collection of stool and water samples and collection of samples through swabbing of hands and utensils.

The team are now comparing their baseline data with the data they have collected after implementation of the intervention and hope to publish the results soon.

Tracy and Kondwani will also be presenting their results at the University of North Carolina Water and Health conference in October 2019.

They will be publishing a paper from the evaluation data which explores actual household practices against reported behaviours. In addition, they will determine the impact of the intervention on diarrhoeal disease incidence in children under five, contamination pathways and household practices.

Kondwani said the following about the study:

“We are looking forward to the final results of our intervention study. We are hoping the results will have a positive influence on national policies related to WASH and nutrition including food hygiene practices in Malawi.”